So there I was, reading Silvia Federici’s bestseller, Caliban and the Witch.1 It argues — to be brief and I hope not unjust — that the witch hunts of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries should be ranked alongside the enclosure of land, the elimination of the commons, the conquest of the New World, and the expansion of the slave trade as a crucial moment in the “primitive accumulation” that made capitalism possible.2 Engaging critically with Marx and rather more critically with Foucault, it’s much maligned (though little reviewed, at least in journals I can get) among academic specialists in many of the subjects it brings together: medieval history, the history of magic, the history of witchcraft, the history of science, the history of political thought, social history, etc. Having read it, I can see why. It draws very selectively on relevant historiography, seeming to prefer dated scholarship with a congenial takeaway to more recent work that might undermine its argument.3 Important factual and interpretative claims are made without reference to evidence or scholarship at all. When they are given, sources are frequently quoted indirectly through other books, and book titles, authors’ names and other details are slightly wrong often enough to suggest unfamiliarity, or sloppiness, or both.4 Phenomena generally regarded as historical myths — such as the ius primae noctis, made famous for my generation by the film Braveheart (1995) — are repeated, without so much as a citation, as accepted, load-bearing truths.5 This is bad history.

Now, I do not think that empirical shortcomings necessarily invalidate a book’s critical or theoretical points; it is possible to be right about Marx or Foucault while being wrong about the Middle Ages or the Inquisition. In my experience, many books are more valuable for the questions they raise, the concepts they describe, or the connections they suggest — the kinds of thing they make it possible to see or think about — than for their specific applications, claims, or conclusions. (This is more or less what I think about a lot of Foucault’s work, albeit he tends to work much more directly and thus verifiably with his primary sources than is the case here.) I wouldn’t cite such a book as an authority for any historical claim. But nor would I throw it across the room unfinished. It says some interesting things, and while these do nothing to mitigate its severe scholarly flaws, they remain interesting all the same. Still, bad history is bad history, and propagating false claims, whatever their provenance, is never good. It would be nice to think that some of the problems evident in the edition I read (the second, revised, Autonomedia one, published in 2014) have been fixed or at least flagged in the Penguin Classics version (published in 2021). Signs point to No.

So there I was, as I said, reading about magic and thinking these and suchlike thoughts, when I came upon the following passage:

Eradicating these practices [i.e. magical practices, ranging from sympathetic magic to divination to love charms] was a necessary condition for the capitalist rationalization of work, since magic appeared as an illicit form of power and an instrument to obtain what one wanted without work, that is, a refusal of work in action. “Magic kills industry,” lamented Francis Bacon, admitting that nothing repelled him so much as the assumption that one could obtain results with a few idle expedients, rather than with the sweat of one’s brow (Bacon 1870: 381).6

My first reaction was: that doesn’t exactly sound like Bacon. Now, some recent and even not-so-recent recent scholarship emphasizes the similarities between the promise of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century “natural magic” to confer power over nature through control of hidden causes, on the one hand, and the goal of an “operative,” productive natural philosophy adumbrated in work like Bacon’s New Atlantis, on the other.7 The latter is full of quasi-impossible technologies for speeding up, slowing down, separating, or combining the forces and the products of nature in useful ways. So neither magic nor Bacon were anything like as simple in their relationship to labor as this passage indicates. But what I meant was more basic than that: “Magic kills industry” did not sound to me like a phrase Bacon would have spoken or written.

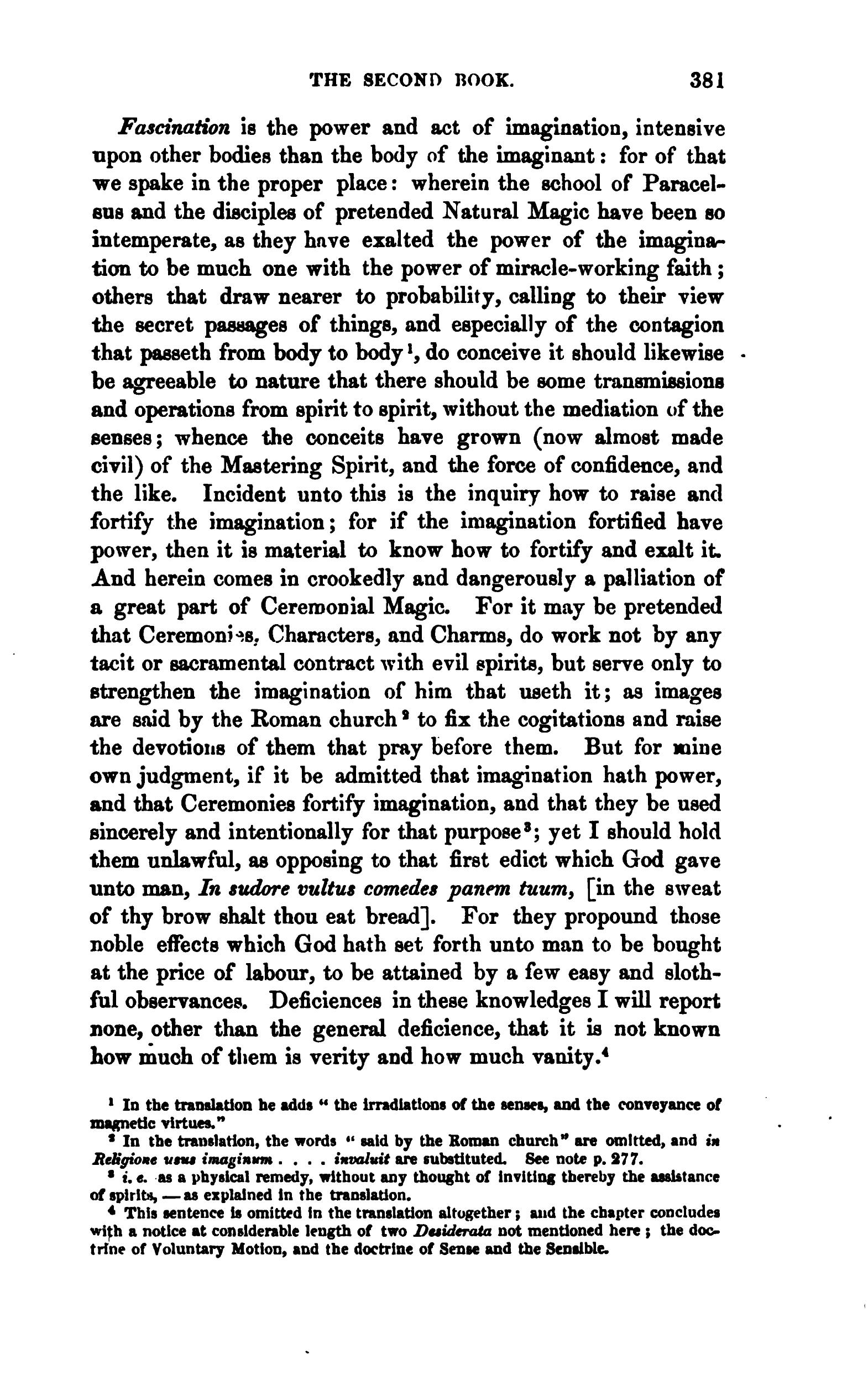

According to the bibliography, “Bacon 1870” refers to The Advancement of Learning as printed in the third volume of the 1870 Longman edition of The Works of Francis Bacon.8 Conveniently, this edition is, with a little searching, available on archive.org. Here is the relevant page:

The first thing to notice is that the ostensible quotation, “Magic kills industry,” does not appear anywhere on the page, nor on the preceding or following pages, nor (so far as I can divine, using text-searchable versions) anywhere in this or any other edition of The Advancement of Learning. So the quotation as a verbatim quotation from the source — and that is what the use of quotation marks is generally understood to mark — is, apparently, made up. Unfortunately, this particular apparently made-up quotation has itself proven highly quotable, turning up in dozens of places online and in print, including in such popular books as David Graeber and David Wengrow’s The Dawn of Everything (mercifully, in an endnote).9

Is “Magic kills industry” perhaps a pithy paraphrase of Bacon’s point? It’s certainly arguable. Bacon is indeed discussing magic here — specifically, “ceremonial magic,” which comes up in a section on “divination” and “fascination” as two spurious types of “Human Knowledge which concerns the Mind”.10 On the second half of the quoted page, Bacon is keen to set some bounds to the power of the imagination and to the proper ways, if any, of fortifying it. As he has noted at the outset of the section, while knowledge of the substance and nature of the mind “may be more really and soundly enquired, even in nature, than it hath been; yet I hold that in the end it must be bounded by religion, or else it will be subject to deceit and delusion”.11 This point is echoed here when Bacon, firmly anti-Catholic, links the pretensions of “Ceremonial magic” to the idolatry of “the Roman church.”12 We then get this:

But for mine own judgment, if it be admitted that imagination hath power, and that Ceremonies fortify imagination, and that they be used sincerely and intentionally for that purpose; yet I should hold them unlawful, as opposing to that first edict which God gave unto man, ‘In sudore vultus comedes panem tuum’ [Genesis 3:19: “In the sweat of thy brow shalt thou eat thy bread”]. For they propound those noble effects which God hath set forth unto man to be bought at the price of labour, to be attained by a few easy and slothful observances.13

Bacon clearly sees the magic of “Ceremonies, Characters, and Charms” as unlawful, regardless of its effectiveness, because it contravenes the divine edict to labour. Is this the same as saying that “Magic kills industry”? There is a kind of family resemblance between not liking magic because it lets workers get away with working less and not liking magic because it violates God’s insistence that people work. But what “repelled” Bacon most was evidently not “the assumption that one could obtain results” without labour, as Federici puts it, but rather that actually doing so in the manner promised by ceremonial magic would contravene divine injunction. Federici’s version loses the religious framing that Bacon insists upon. Nor does it take into account Bacon’s more complicated engagement with “natural magic” elsewhere in the same book; all magic may be magic for Federici, but it was not so simple for Bacon or his contemporaries.14 As a paraphrase, then, “Magic kills industry” is at best a tendentious, though arguable, oversimplification. But then, it’s not pretending to be a good or even a defensible paraphrase. It’s pretending to be a direct quotation.

A reader may, of course, feel that Federici still gets Bacon fundamentally right. One may well believe that the religious context he offered for his righteous dismissal of ceremonial magic was, after all, but so much ideology obscuring the material interests of incipient capitalism, from his readers and even from himself. One may certainly think, as I do myself, that Baconian science had a lot to do with the exploitation of labour, with new and newly destructive views of nature, and more generally with the rise of capitalism in the seventeenth century. That’s all fine, as far as it goes. Virtually any use of a primary source involves some interpretation, and it is not unusual for a source to conceal or simply fail to state its motives, assumptions, or implications. There are often good reasons for not taking a source at its word. But in order to judge such an interpretative decision critically, indeed to judge it at all, one has to be aware of it in the first place. A pithy and apparently direct quotation permits no such questioning. And often, by the time someone thinks to look it up in the purported source, it has multiplied beyond control.

P.S. If the sloppiness of the book is already common knowledge among specialists, why was I reading it? Well, one likes to know why things have the reputations they do, and ideally to be able to form an independent judgment rather than merely repeat what someone else, even many qualified someone elses, has said about them. (This is, after all, part of the idea behind scholarly norms such as consulting your sources directly and quoting them accurately!) But, to be honest, what put it on my summer list was that over the last few years several students have asked about it, drawn in by its arguments but — some of them, anyway — wary of its historical claims. There is a certain amount of sustained, critical online commentary, but little of it in “official” academic venues and much of it either anonymous, or, like so much of the book’s own evidence, secondhand. The fact that specialists are aware of something does not mean their students are, and the fact that critiques are publicly available is of little force when even more praise, some of it from big-name academics, is as or more accessible. We are talking about a Penguin Modern Classic here! Sadly, as I have also learned, the fact that a misquotation or fabrication can be made evident to anyone who looks does not mean it will be corrected, even in a much less popular book. That’s life. It’s off my plate, anyway.

- Silvia Federici, Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation, 2nd ed. (Brooklyn: Autonomedia, 2014). ↩︎

- Statements abound; see, e.g., ibid., 165. ↩︎

- Discussing the shortcomings of historiography of witchcraft — much of it written, in Federici’s view, by “worthy heirs of the 16th-century demonologists” — Federici gives only H. Erik Midelfort’s Witch-Hunting in Southwestern Germany (1972) and F. G. Alexander and S. T. Selesnick’s 1978 History of Psychiatry (the latter quoted indirectly, through Mary Daly’s 1978 Gyn/Ecology: The MetaEthics of Radical Feminism) as examples. This is thin evidence by which to judge what was, when Caliban and the Witch was first published in 2004, a very deep body of literature. Federici, Caliban and the Witch, 163-4. ↩︎

- William Petty, for instance, is referred to as writing “(using Hobbes’ terminology) Political Arithmetics.” So far as I am aware, Petty’s phrase “political arithmetic” was his own coinage, not Hobbes’s, and was regarded as such by contemporaries familiar with both. (It is possible that Federici is here repeating someone else’s claim.) Federici, Caliban and the Witch, 146. For a representative string of secondhand quotation, see for example ibid., 150-4. ↩︎

- Arguing that medieval women’s subordination to their husbands and fathers was mitigated by the men’s subordination to feudal lords — an important point, since part of the larger argument is that capitalism radically increased patriarchal authority in the household — Federici writes: “It was the lord who commanded women’s work and social relations, deciding, for instance, whether a widow should remarry and who should be her spouse, in some areas even claiming the ius primae noctis — the right to sleep with a serf’s wife on her wedding night.” Ibid., 25. ↩︎

- Ibid., 142. Italics in original. ↩︎

- Among books available before 2004, these connections were made in works by Frances Yates including Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1964), The Occult Philosophy in the Elizabethan Age (London: Routledge, 1979), and, most contentiously, The Rosicrucian Enlightenment (London: Routledge, 1972); and then more recently by William Eamon, Science and the Secrets of Nature: Books of Secrets in Medieval and Early Modern Culture (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994). Federici does cite Yates’s Giordano Bruno, but on the powers attributed to witches rather than on the legacy of magic or hermeticism in later science: Federici, Caliban and the Witch, 198. ↩︎

- Francis Bacon (ed. James Spedding, Robert Leslie Ellis, and Douglas Denon Heath), The Works of Francis Bacon, New edition, vol. III (London: Longmans & Co., 1870). ↩︎

- David Graeber and David Wengrow, The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity (New York: Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux, 2021), 574-5, n.50. ↩︎

- Pages 379-81 in the 1870 edition; or see Brian Vickers (ed.), Francis Bacon: A Critical Edition of the Major Works (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), 215-17. ↩︎

- Vickers (ed.), Francis Bacon, 215. ↩︎

- Ibid., 217. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- See Vickers (ed.), Francis Bacon, 193, 201-2. ↩︎